OS Notes: Memory Management

Memory abstraction

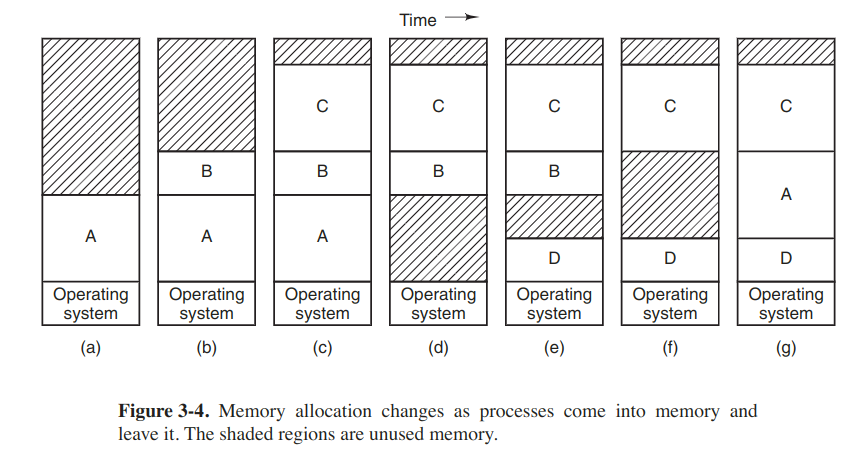

Swapping

Bringing in each process in its entirety, running it for a while, then putting it back on the disk.

How much memory should be allocated for a process when it is created or swapped is worth making concerns.

Memory compaction

When swapping creates multiple holes in memory, it is possible to combine them all into one big one by moving all the processes downward as far as possible. It is usually not done because requiring a lot of CPU time.

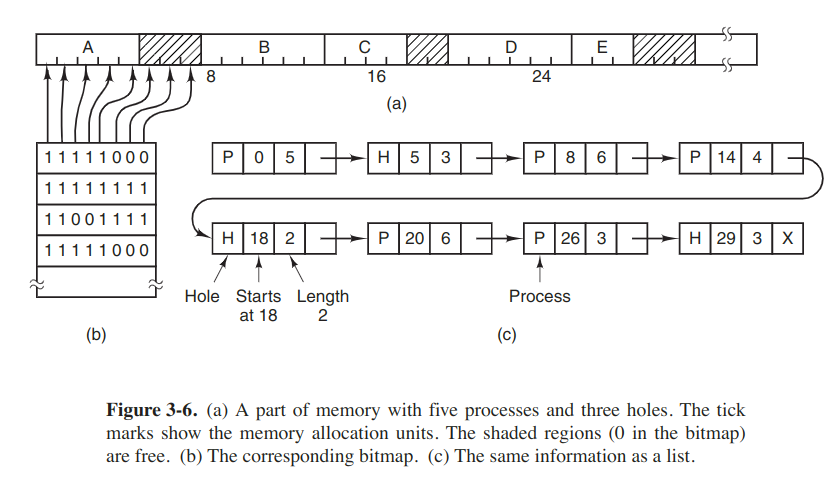

Managing free memory

With bitmaps

The size of the allocation unit is an import design issue. The smaller the allocation unit, the larger the bitmap. But if the allocation unit is chosen large, appreciable memory may be wasted in the last unit of the process if the process size if not an exact multiple of the allocation unit.

The main problem is searching a bitmap for a run of a given length is a slow operation.

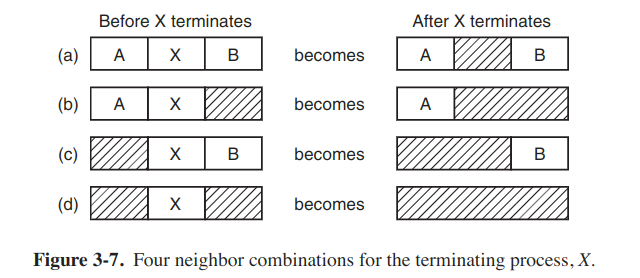

With linked lists

Double-linked list makes it easier to find the previous entry and to see if a merge is possible.

First fit

The memory manager scans along the list of segments until if finds a hole that is big enough.

Next fit

It works the same way as first fit, except that it keeps track of where it is whenever it finds a suitable hole. The next time it is called to find a hole, it starts searching the list from the place where it left off last time, instead of always at the beginning.

Simulations by Bays (1977) show that next fit gives slightly worse performance than first fit.

Best fit

It searches the entire list and takes the smallest hole that is adequate.

FIrst fit and next fit generate large holes on the average because best fit tends to fill up memory with tiny, useless holes.

Worst fit

It always takes the largest available hole. However, simulation has shown that worst fit is not a very good idea either.

Speed up

Maintaining separate lists for processes and holes. The inevitable price that is paid for this speedup on allocation is the additional complexity and slowdown when deallocating memory.

The hole list may be kept sorted on size, hence first fit and best fit are equally fast, and next fit is pointless.

Quick fit

It maintains separate lists for some of the more common sizes requested, hence finding a hole of the required size is extremely fast. But as all schemes that sort by hole size, namely, when a process terminates or is swapped out, finding its neighbors to see if a merge with them is possible is quite expensive.

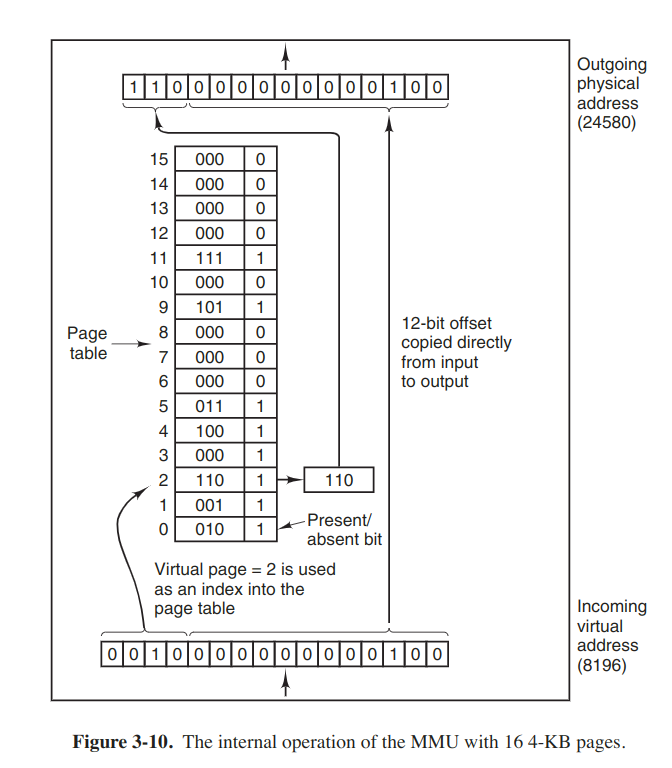

Virtual memory

The basic idea behind virtual memory is that each program hasits own address space, which is broken up into chunks called pages. Each page is a contiguous range of addresses. These pages are mapped onto physical memory, but not all pages have to be in physical memory at the same time to run the program.

When virtual memory is used, the virtual addresses go to an MMU (Memory Management Unit) that maps the virtual addresses onto the physical memory addresses. The virtual address space consists of fixed-size units called pages. The corresponding units in the physical memory are called page frames. Many processors support multiple page sizes that that can be mixed and matched as the os sees fit. In the actual hardware, a Present/absent bit keeps track of which pages are physically present in the memory.

If the process references an unmapped address, the MMU notices that and causes the CPU to trap to the operating system. This trap is called a page fault. The os picks a little-used page frame and writes its contents back to the disk. It then fetches the page that was just referenced into the page frame just freed, changes the map, and restarts the trapped instruction.

Page tables

The page number is used as an index into the page table, yielding the number of the page frame corresponding to that virtual page. In a simple impl, the mapping of virtual addresses onto physical addresses can be summarized as follows: the virtual address is split into a virtual page number and an offset. The virtual page number is used as an index into the page table to find the entry for that virtual page. From the page table entry, the page frame number (if any) is found. THe page frame number is attached to the high-order end of the offset, replacing the virtual page number, to form a physical address that can be sent to the memory.

Mathematically speaking, the page table is a function, with the virtual page number as argument and the physical frame number as result.

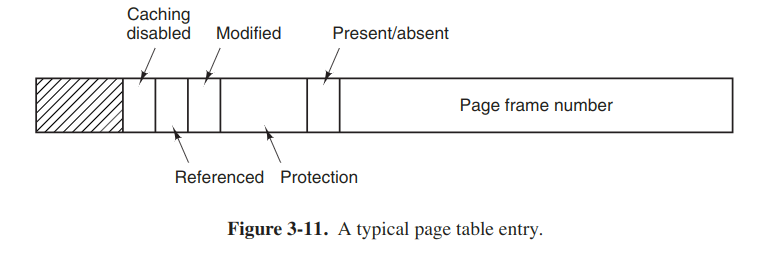

Structure of an entry

The Protection bits tell what kinds of access are permitted.

The Modified and Referenced bits keep track of page usage. When a page is written to, the hardware automatically sets the Modified bit. If the page in it has been modified, it must be written back to the disk when the os decdes to reclaim a page frame. The bit is sometimes called the dirty bit.

The Referenced bit is set whenever a page is referenced, either for reading or for writing. The bit plays an important role in several of the page replacement algorithms.

The last bit allows caching to be disabled for the page. It's important for pages that map onto device registers rather than memory.

Speeding up paging

Two major issues:

- The mapping from virtual address to physical address must be fast.

- If the virtual address space is large, the page table will be large.

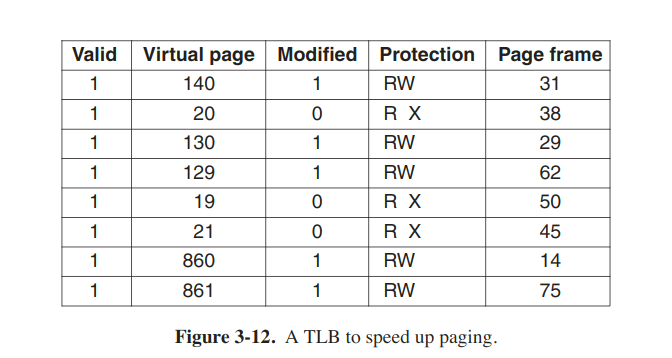

Translatation Lookaside Buffer (TLB)

To equip computers with a small hardware device for mapping virtual addresses to physical addresses without going through page table. The device, called a TLB or sometimes an associative memory.

When a virtual address is presented to MMU to translation, the hardware first checks to see if its virtual page number is present in the TLB by comparing it to all the entries simultaneously. Doing so requires special hardware, which all MMUs with TLBs have. If a valid match is found and the access does nt violate the protection bits, the page frame is taken directly from the TLB, without going to the page table.

When the virtual page number is not in the TLB, the MMu detects the miss and does an ordinary page table lookup. It then evicts one of the entries from the TLB and replaces it with the page table entry just looked up.

When an entry is purged from the TLB, the modified bit is copied back into the page table entry in memory.

Page tables for large memories

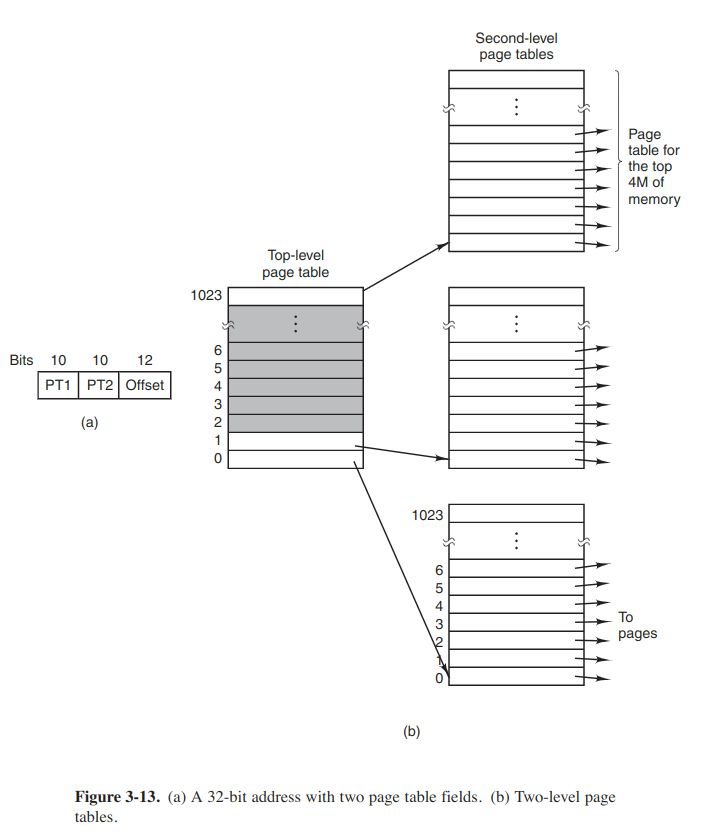

Another problem is how to deal with very large virtual address spaces.

Multilevel page tables

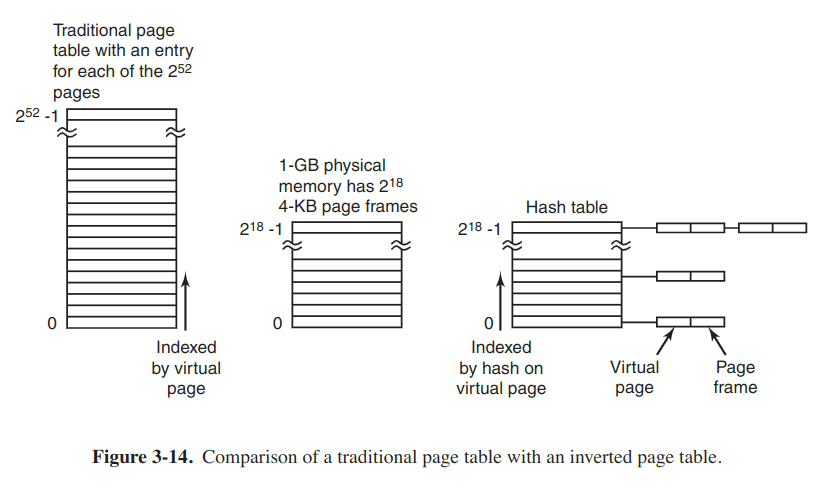

Inverted page tables

In this design, there is one entry per page frame in real memory, rather than one entry per page of virtual address space. The entry keeps track of which (process, virtual page) is located in the page frame.

Although inverted page tables save lots of space, virtual-to-physical translation becomes much harder. The hardware must search the entire inverted page table on every memory reference.

The way out of the dilemma is to make use of the TLB. On a TLB miss, the inverted page table has to be searched in software. One feasible way to accomplish this search is to have a hash table hashed on the virtual address. All the virtual pages currently in memory that have the same hash value are chained together.

Page replacement algorithms

The problem occurs in other areas of computer design as well.

The optimal page replacement algorithm

Not recently used (NRU)

Most computers with virtual memory have two status bits, R & M, associated with each page. Periodically, the R bit is cleared, to distinguish pages that have not been referenced recently from thos that have been.

First-in, first-out (FIFO)

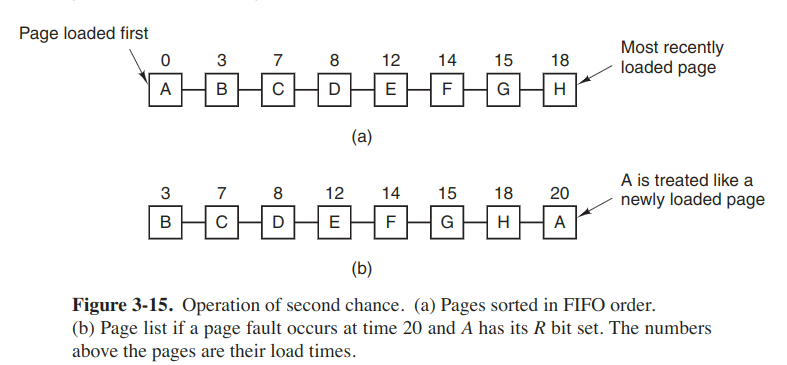

Second-chance

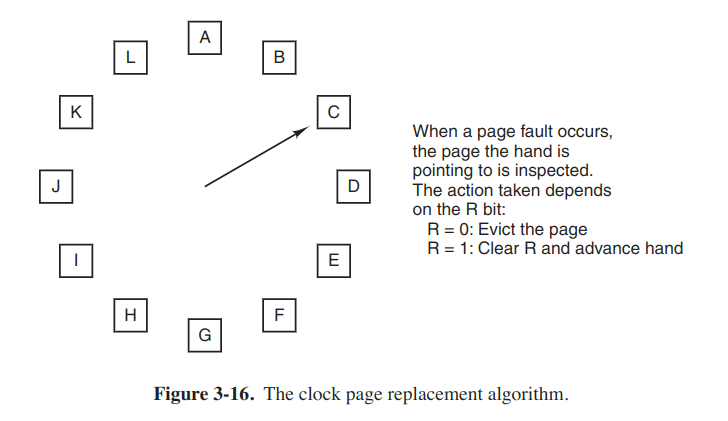

Clock

Least recently used (LRU)

Remind me of the interview at Bytedance.

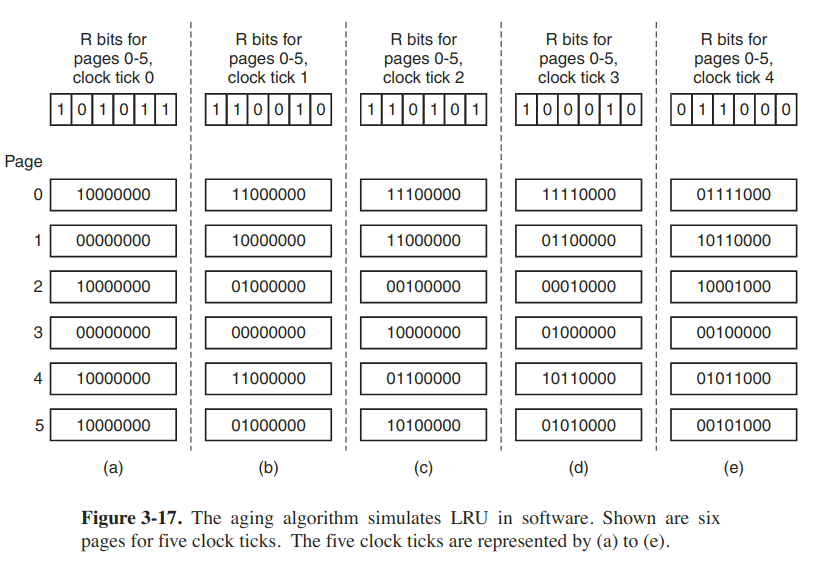

Simulating LRU - NFU (not frequently used)

It requires a software counter associated with each page, initially zero. At each clock interrupt, the os scans all the pages in memory. For each page, the R bit, which is 0 or 1, is added to the counter. The comters roughly keep track of how often each page has been referenced. When a page fault occurs, the page with the lowest counter is chosen for replacement.

Simulating LRU - Aging

Differences between LRU & NFU

- By recording only 1 bit per time interval, lose the ability to distinguish references early in the clock interval from those occuring later.

- In aging the counters have a finite number of bits, which limits its past horizon.

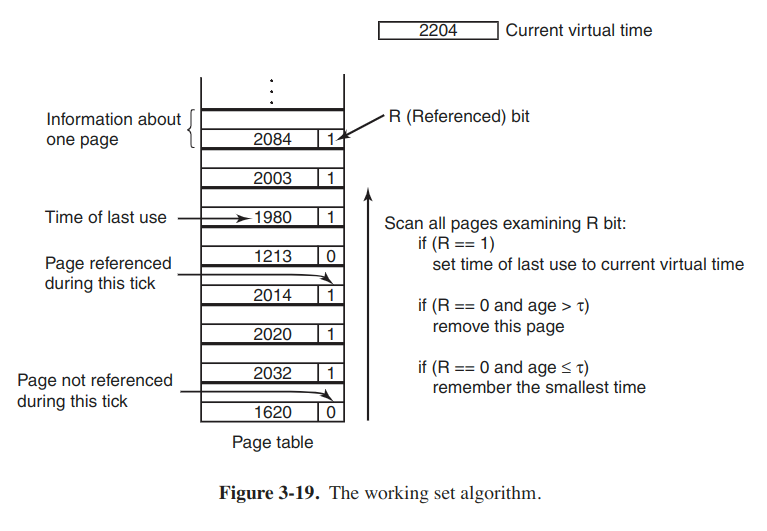

Working set

Concepts: demand paging, locality of reference, thrashing, prepaging, current virtual time.

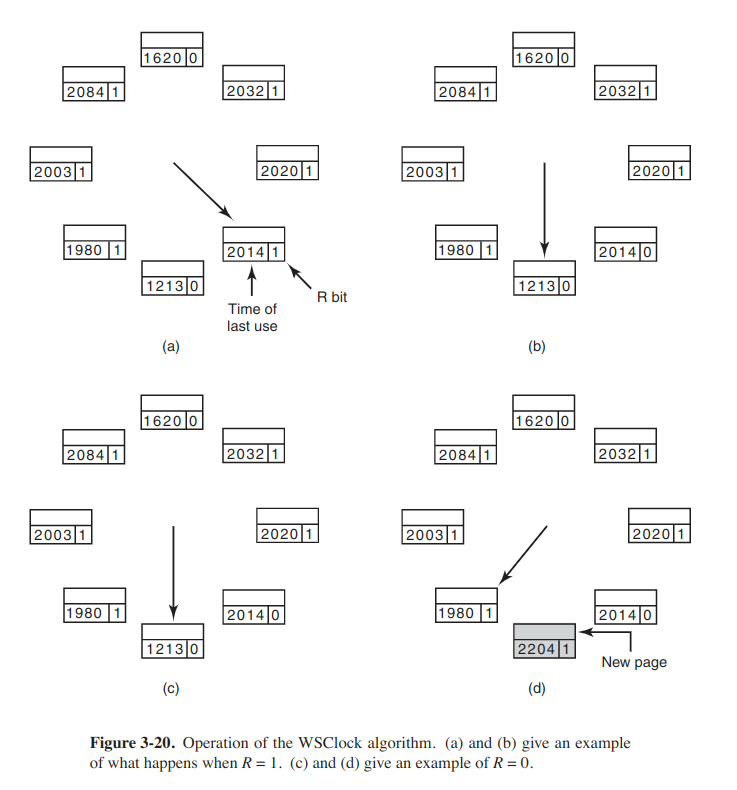

WSClock

The basic working set algorithm is cumbersome, since the entire page table has to be scanned at each page fault until a suitable candidate is located.

When the page pointed to has R = 0, if the age is greater than τ and the page is clean, it is not in the working set and a valid copy exists on the disk. On the other hand, if the page is dirty, to avoid a process switch, the write to disk is scheduled, but the hand is advanced and the algorithm continues with the next page.

Summary

| Algorithm | Comment |

|---|---|

| Optimal | Not implementable, but useful as a benchmark |

| NRU | Very crude approximation of LRU |

| FIFO | Might throw out impormant pages |

| Second chance | Big improments over FIFO |

| Clock | Realistic |

| LRU | Execellent but difficult to implement exactly |

| NFU | Fairly crude approximation to LRU |

| Aging | Efficient algorithm that approximates LRU well |

| Working set | Somewhat expensive to implement |

| WSClock | Good efficient algorithm |

Design issues for paging systems

Local versus global allocation policies

In general, global algorithms work better, especially when the working set size can vary a lot over the lifetime of a process.

If a local algorithm is used and the working set grows, thrashing will result, even if there are a sufficient number of free page frames. It the working set shrinks, local algorithms waste memory.

If a global algorithm is used, the system must continually decide how many page frames to assign to each process. One way is to have an algorithm for allocating page frames to processes. PFF (Page Fault Frequency) algorithm tells when to increase or decrease a process' page allocation but says nothing about which page to replace on a fault. It just controls the size of the allocation set.

Local Control

Even with the best algorithm, it can happen that the system thrashes. A good way to reduce the number of processes competing for memory is to swap some of them to the disk and free up all the pages they are holding until the thrashing stops.

However, another factor to consider is the degree of multiprogramming. When the number of processes in main memory is too low, the CPU may be idle for sustantial periods of time. This consideration argues for considering not only process size and paging rate when deciding which process to swap out, but also its characteristics, such as whether it is CPU bound or I/O bound and so on.

Page size

Two factors argue for a small page size

- A randomly chosen text, data, or stack segment will not fill an integral number of pages. The extra space in that page is wasted, which is called internal fragmentation.

- Considering a program consisting of several sequential phases needing few memory each. A large page size will cause more wasted space to be in memory than a small one.

On the other hand

- Small pages mean that programs will need many pages, and thus a large page table.

- Small pages use up much valuable space in the TLB.

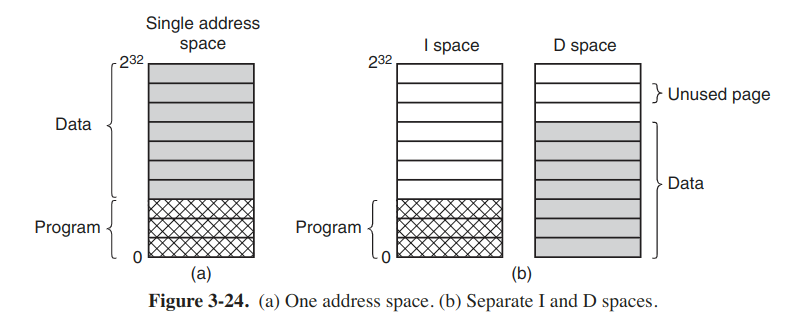

Separate instruction and data spaces

Shared pages

If separate I- and D-spaces are supported, it is relatively straightforward to share programs by having two or mor eprocesses use the same page table for their I-space but different page tables for their D-spaces.

Special data structures are needed to keep track of shared pages, especially if the unit of sharing is the individual page, rather than an entire page table.

In UNIX, after a fork system call, the parent and child are required to share both program text and data. In a paged system, what is often done is to give each of these processes its own page table and have both of them point to the same set of pages. Thus no copying of pages is done at fork time. However, all the data pages are mapped into both processes as read only.

As soon as either process updates a memory word, the violation of the read-only protection causes a trap to the os. A copy is then made of the offending page so that each process now has its own private copy. Both copies are now set to READ/WRITE, so subsequent writes to either copy proceed without trapping. This approach is called copy on write.

Shared libraries

Shared libraries are called DLLs or Dynamic Link Libraries on Windows.

When a program is linked with shared libraries, instead of including the actual function called, the linker includes a small stub routine that binds to the called function at run time. Shared libraries are loaded either when the program is loaded or when functions in them are called for the first time. If another program has already loaded the shared library, there is no need to load it again.

If a function in a shared library is updated to remove a bug, it is not necessary to recompile the programs that call it.

However, since the library is shared , relocation on the fly (using absolute addresses) will not work. A solution is to compile shared libraries with a pecial compiler flag telling the compiler only to produce instructions using relative addresses. Code that uses only relative offsets is called postion-independent code.

Mapped files

Memory-mapped files can be accessed as a big character array in memory. Multiple processes that map onto the same file at the same time can communicate over shared memory.

Cleaning policy

To ensure a plentiful supply of free page frames, paging systems generally have a background process, called the paging daemon, that sleeps most of the time but is awakened periodically to inspect that state of memory. At the very least, the daemon ensures that all the free frames are clean, so they need not be written to disk in a big hurry when they are required.

A possible implementation is with a two-handed clock. The front hand is controlled by the daemon. When it points to a dirty page, that page is written to the disk and the hand is advanced. When pointing to a clean one, it is advanced. The back hand is used for page replacement, as in the standard clock algorithm.

Virtual memory interface

In some advanced systems, programmers have some control over the memory map and can use it to enhance program behavior.

- Control over the memory map allow multple processes share the same memory, so high bandwidth sharing becomes possible.

- Sharing of pages can be used to implement a high-performance message-passing system. A message can be passed by having the sending process unmap the page containing message, and the receiving process mapping them in.

- Distributed shared memory

Implementation issues

OS involvement with paging

Process creation

The os has to determine how large the program and data will be, create and initialize a page table for them. Space has to be allocated in the swap area on disk so that when a page is swapped out, it has somewhere to go. The swap area also has to be initialized with program text and data so that when the new process starts getting page faults, the pages can be brought in. Some systems page the program text directly from the exe, thus saving disk space and initialization time. Finally, info about the page table and swap area on disk must be recorded in the process table.

Process execution

When a process is scheduled for execution, the MMU has to be reset for the new process and the TLB flushed, to get rid of traces of the previously executing process. The new process' page table has to be made current, usually by copying it or a pointer to it to some hardware register. Optionally some or all the process' pages can be brought into memory to reduce the number of page faults initially.

Page fault

When a page fault occurs, the os has to read out hardware registers to determine which virtual address caused the fault. From the info, it must compute which page is needed and locate that page on disk. It must then find an available page frame in which to put the new page, evicting some old page if need be. Then it must read the needed page into the page frame. Finally, it must back up the program counter to have it point to the faulting instruction and let that instruction execute again.

Process termination

The os must release its page table, pages and the disk space that the pages occupy when they are on disk. If some of the pages are shared with other processes, the pages in memory and on disk can be released only when the last process using them has terminated.

Page fault handling in detail

- The hardware traps to the kernel, saving the program counter on the stack.

- An assembly-code routine is started to save the general registers and other volatile info, to keep the os from destroying it. This routine calls the os as a procedure.

- The os discovers that a page fault has occured, and tries to dicover which virtual page is needed. Mostly this info is contained in one of the hardware registers, or the os must retrieve the program counter and figure out what it was doing when the fault hint.

- The system checks if this address is valid and the protection is consistent with the access and if there is a free page frame.

- If the page frame selected is dirty, the page is scheduled for transfer to disk, and a context switch takes place, suspending the faulting process and letting another one run until the disk transfer has completed. The frame is marked as busy to prevent it from being used for another purpose.

- The os then looks up the disk address where the needed page is, and schedules a disk operation to bring it in. Again, the faulting process is still suspended.

- When the disk interrupt indicated that the page has arrived, the page tables are updated and the frame is marked as normal.

- The faulting instruction is backed up to the state it had when it began and the program counter is reset to point to that instruction.

- The faulting process is scheduled, and the os returns to the routine that called it (assembly-code routine).

- This routine reloads the registers and other info, and returns to user space to continue execution.

Instruction backup

When a program references a page that is not in memory, the instruction causing the fault is stopped partway through and a trap to the os occurs. After the os has fetched the page needed, it must restart the instruction causing the trap.

The os has no way of telling whether the address is part of an address or an single opcode. Besides, some modes use autoincrementing, which means that a side effect of executing the instruction is to increment on or more registers.

Some CPU designers provide a solution, usually in the form of hidden internal register into which the program counter is copied just before each instruction is executed. They may also have a second register telling which registers have already been autoincremented or autodecremented.

Locking pages in memory

If the paging algorithm is global, there is chance that the page containing the I/O buffer will be chosen to be removed from memory. If an I/O device is currently in the process of doing DMA transfer to that page, removing it will cause part of the data to be written in the buffer where they belong, and part of the data to be written over the just-loaded page.

One solution is to lock pages, which is called pinning it in memory, engaged in I/O in memory so that they will not be removed.

Another is to do all I/O to kernel buffers and then copy the data to user pages later.

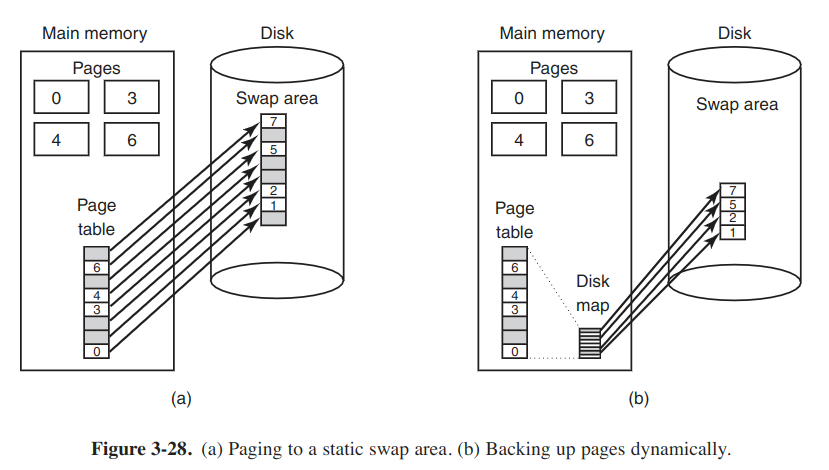

Backing store

Here we discuss about where on the disk the page, which is selected for removal, is put when it is paged out.

The simplest algorithm is to have a special swap partition on the disk. When the system is booted, the swap partition is empty and is represented in memory as a single entry giving its origin and size. When the first process started, a chunk of the partition area the size of the first process is reserved and the remaining area reduced by that amount. As new processes are started, they are assigned chunks of swap partition equal in size to their core images.

Before a process can start, the swap area must be initialized. One way is to copy the process image to the swap area, so that it can be brought in as needed. The other is to load the entire process in memory and let it be paged out as needed.

However, the problem is that processes can increase in size after starting. It can be better to reserve separate swap areas for the text, data and stack and allow each of these areas to consist of multiple chunk on the disk.

Another solution is to allocate nothing in advance and allocate disk space for each page when it is swapped out and deallocate it when swapped bak in. The disadvantage is that a disk address is needed in memory to keep track of each page on disk.

These two alternatives are shown as follows:

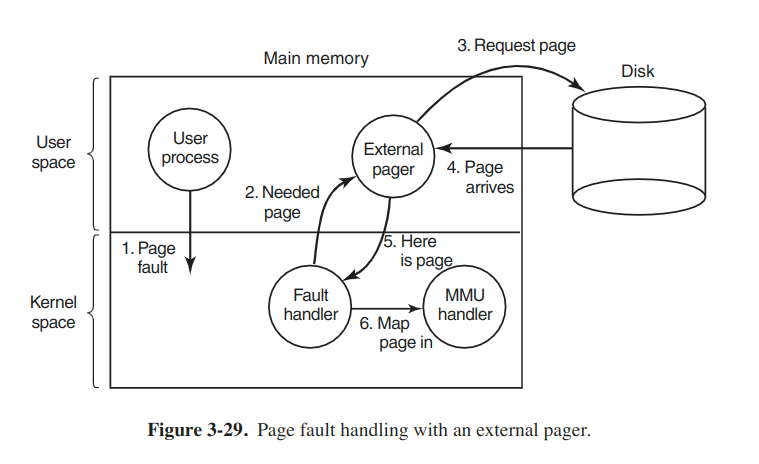

Separation of policy and machanism

A simple example of the memory management system divided into 3 parts:

- A low-level MMU handler.

- A page fault handler that is part of the kernel.

- An external pager running in user space.

When a process starts up, the external pager is notified to set up the process' page map and allocate necessary backing store on the disk.

Segmentation

Segments are some completely independent address spaces, which consists of a linear sequence of addresses, starting at 0 and going up to some maximum value.

A segmented memory simplifies the handling of data structures that are growing and shrinking. Besides, the linking of procedures compiled separately is greatly simplified. If the procudure in segment n is modified and recompiled, no other procedures need be changed.

In a segmented system, the shared library can be put in a segment and shared by multiple processses, while it is more complicated to have shared libraries in pure paging systems simulating segmentation too.

Implementation of segmentation differs from paging in an essential way: pages are of fixed size and segments are not. After the system running for a while, memory will be divided into several chunks, Which phenomenon called checkerboarding or external fragmentation.

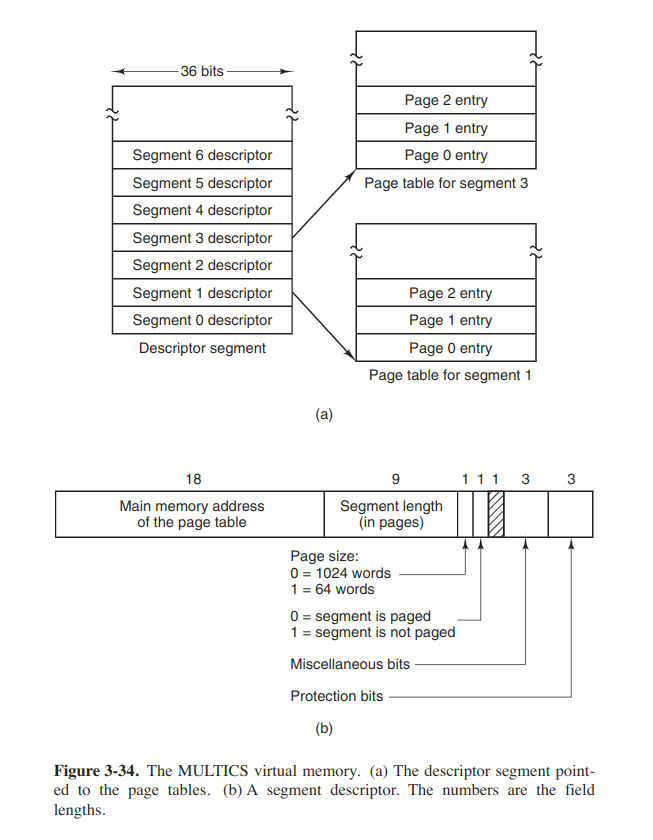

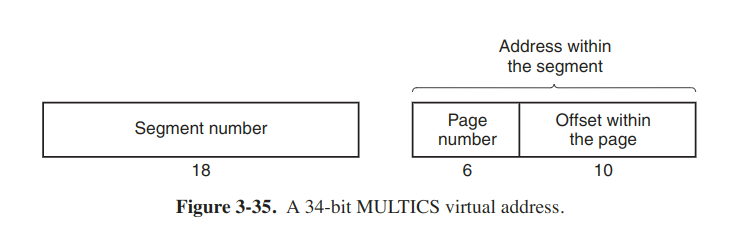

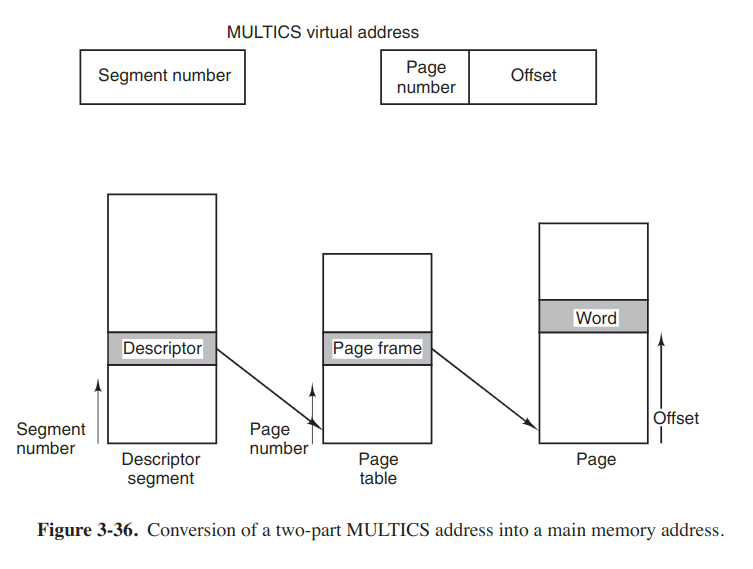

Segmentation with paging: MULTICS

If the segments are large, it may be inconvenient to keep them in main memory entirely. This leads to the idea of paging them. MULTICS is one of the several significant systems that supports paged segments. MULTICS treat each segment as a virtual memory and page it, combining the advantage of paging (uniform page size and not having to keep the whole segment in memory if only part of it was being used) with the advantages of segmentataion (ease of programming, modularity, protection, sharing).

A segment descriptor contained an indication of whether the segment was in main memory or not. If any part of the segment was in memory, the segment was considered to be in memory, so is its page table.

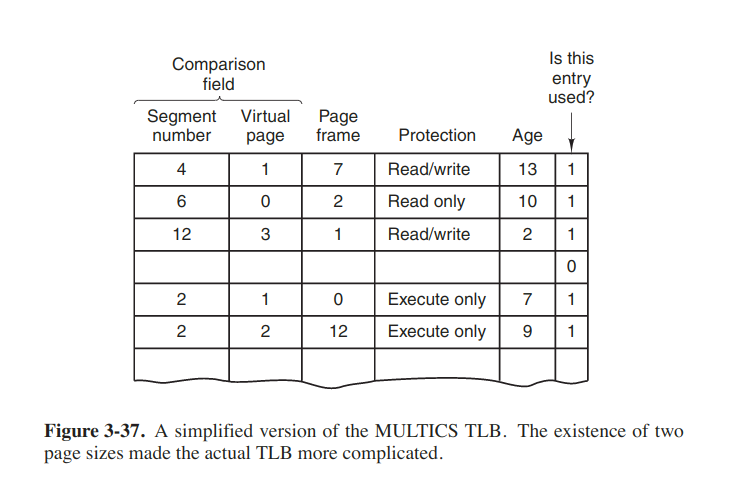

If the preceding algorithm were actually carried out by the os on every instruction, programs would not run very fast. In reality, the MULTICS hardware contained a 16-word high-speed TLB that could search all its entries in parallel for a given key.

Segmentation with paging: the Intel x86

Whereas MULTICS had 256K independent segments, each up to 64K 36-bit words, the x86 has 16K independent segments, each holding up to 1 billion 32-bit words. As of x86-64, segmentation is considered obsolete and is no longer supported, except in lacy mode.

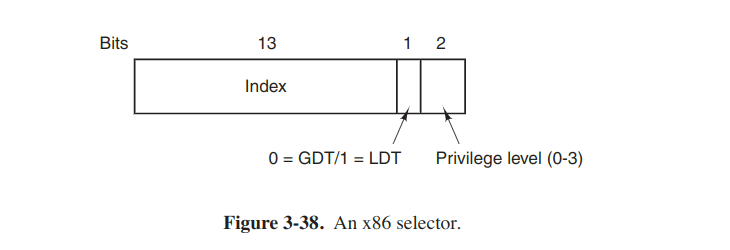

The core of the x86 virtual memory consists of two tables, called the LDT (Local Descriptor Table) and the GDT (Global Descriptor Table). Each program has its own LDT, but there is a single GDT, shared by all the programs on the computer. The LDT describes segments local to each program, including its code, data, stack and so on, whereas the GDT describes system segments, including the os itself.

To access a segment, an x86 program first loads a selector for that segment intoone of the machine’s six segment registers. During execution, the CS register holds the selector for the code segment and the DS register holds the selector for the data segment.

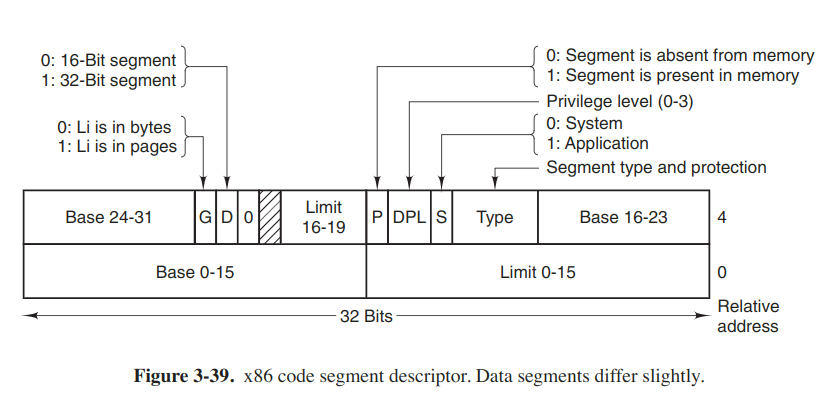

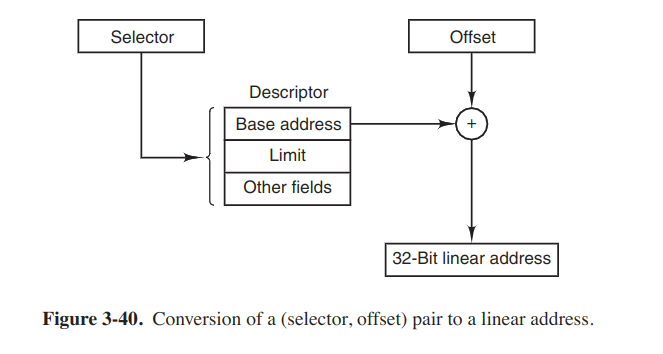

At the time a selector is loaded into a segment register, the corresponding descriptor is fetched from the LDT or GDT and stored in microprogram registers, soit can be accessed quickly. A descriptor consists of 8 bytes, including the segment’s base address, size, and other information.

As soon as the microprogram knows which segment register is being used, it can find the complete descriptor corresponding to that selector in its internal registers. If the segment does not exist, or is currently paged out, a trap occurs.

The hardware then uses the Limit (length of segment) field to check if the offset if beyond the end of the segment, in which case a trap also occurs. Logically, there should be a 32-bit field in the descriptor giving the size of the segment, but only 20 bits are available, so a different scheme is used. If the Gbit (Granularity) field is 0, the Limit field is the exact segment size, up to 1MB. If it is 1, the Limit field gives the segment size in pages instead of bytes. With a page size of 4 KB, 20 bits are enough for segments up to $2^{32}$ bytes.

Assuming that the segment is in memory and the offset is in range, the x86 then ads the 32-bit Base field in the descriptor to the offset to form what is called a linear address. The Base field is broken up into 3 pieces.

If paging is disabled (by a bit in a global control register), the linear address is interpreted as the physical address and sent to the memory for the read or write. Thus with paging disabled, we have a pure segmentation scheme, with each segment's base address given in its descriptor. Segments are not prevented from overlapping for it takes too much time to verify that they were disjoint and would be too much trouble.

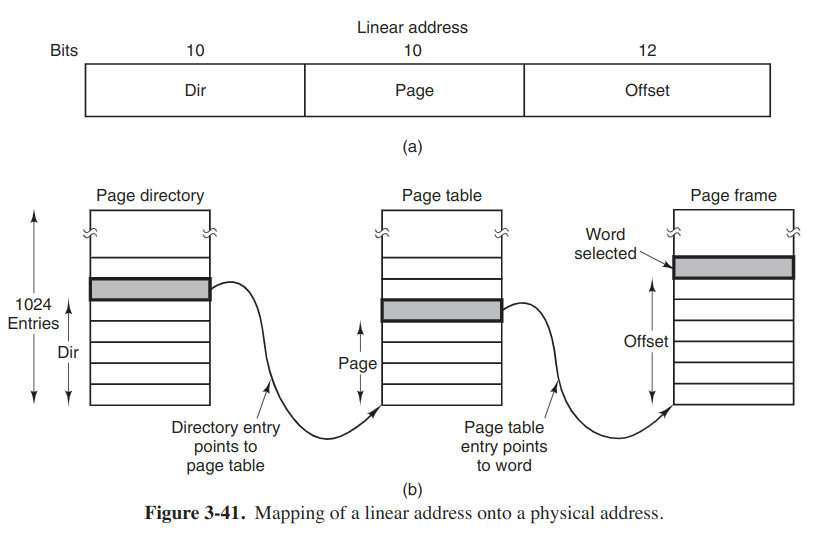

On the other hand, if paging is enabled, the linear address is interpreted as a virtual address and mapped onto the physical address using page tables. Here a two-level mapping is used to reduce the page table size for small segments.

Each running program has a page directory consisting of 1024 32-bit entries. It is located at an address pointed to by a global register. Each entry in this directiory points to a page table also containing 1024 32-bit entries. The page table entries point to page frames.

Each page table has entries for 1024 4-KB page frames, so a single page table handles 4 MB of memory. A segment shorter than 4M will have a page directory with a single entry, a pointer to its one and only page table.

To avoid making repeated references to memory, the x86 has a small TLB that directly maps the most recently used Dir-Page conbinations onto the physical address of the page frame.

It is also worth noting that if some application does not need segmentation but is simply content with a single, paged, 32-bit address space, that model is possible.All the segment registers can be set up with the same selector, whose descriptor has Base=0 and Limit set to the maximum. The instruction offset will then be the linear address, with only a single address space used — in effect, normal paging.