OS Notes: File Systems

Some file systems distinguish between upper- and lowercase letters, whereas others do not. UNIX falls in the first category, while the old MS-DOS falls in the other. Windows 95 and Windows 98 both used the MS-DOS file system, called FAT-16. Windows 98 introduced some extensions to FAT-16, leading to FAT-32, but these two are quite similar. The following sieries of Windows all support both FAT file systems which are really obsolete now. These os also have a much more advanced native file system (NTFS) that has different properties. There is also second file system for the server version of Windows 8, known as ReFS (or Resilient File System). There is also a new FAT-like file system, named exFAT, a Microsoft extension to FAT-32 that is optimized for flash drives and large file systems.

Implementation

File-system layout

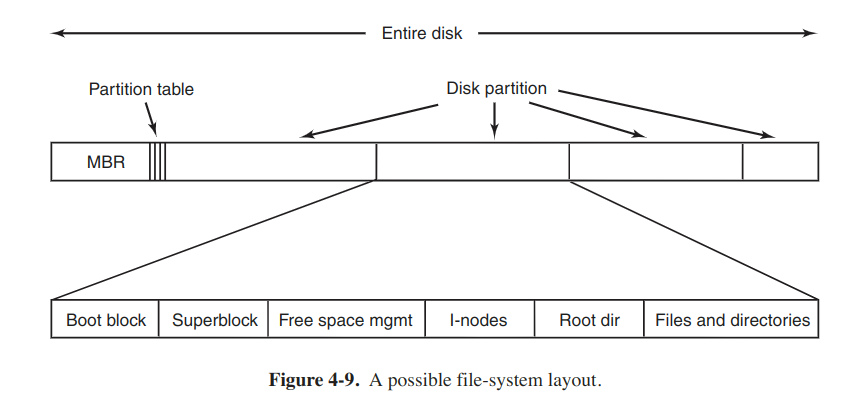

Most disks can be divided up into one or more partitions, with independent file systems on each partition. Sector 0 of the disk is called MBR (Master Boot Record) and is used to boot the computer. The end of the MBR contains the partion table. This table gives the starting and ending addresses of each partition. One of the partitions in the table is marked as active. When the computer is booted, the BIOS reads in and executes the MBR. The first thing the MBR program does is to locate the active partition, read in its first block, which is called the boot block, and execute it. The program in the boot block loads the os in that partition. For uniformity, every partition contains a boot block even if it does not contain a bootable os.

Often the file system contains some of the items shown in the above figure. The first one is the superblock, which contains all the key parameters about the file system and is read into memory when the computer is booted or the file system is first touched. Typical information includes a magic number to identify the file-system type, the number of blocks and so on.

Implementing files

Probably the most importmant issue is keeping track of which disk blocks go with which file. A few of methods are shown as follows.

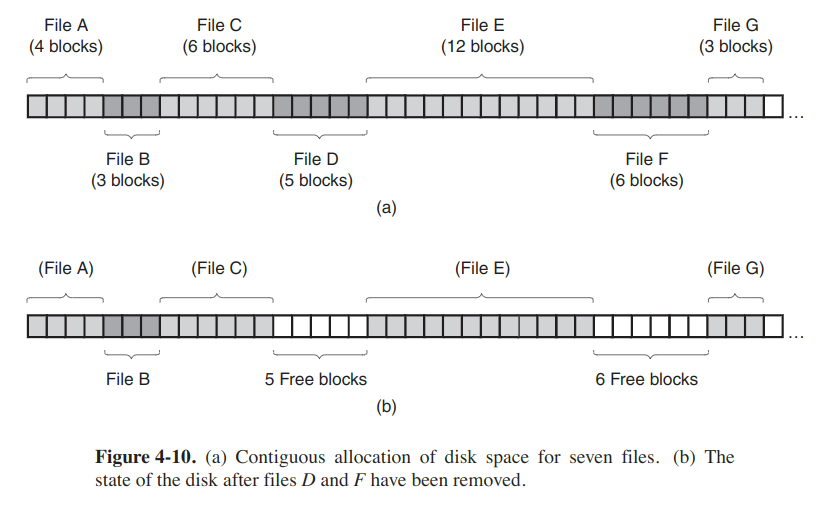

Contiguous allocation

The scheme is to store each file as a contiguous run of disk blocks.

Pros:

- Simple to implement because track of where a file's blocks are is reduced to remember two numbers: the disk address of the first block and the number of blocks.

- The read performance is excellent because the entire file can be read from the disk in a single operation. Only one seek (to the first block) is needed, so data come in at the full bandwidth of the disk.

Cons:

- Over the course of time, the disk is ultimately fragmented. When the disk is filled up, it become necessary to either compact the disk, which is prohibitively expensive, or to reuse the free space in the holes. But when a new file is to be created, it is necessary to know its final size to choose a hole to place it in.

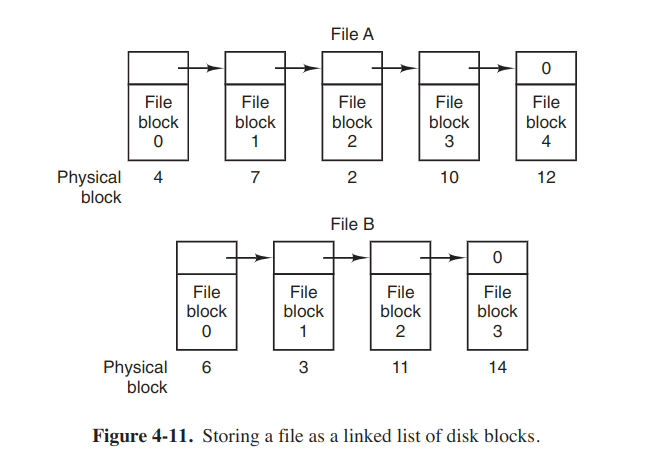

Linked-list allocation

The method is to keep each one as a linked list of disk blocks.

Pros: No space is lost to disk fragmentation.

Cons:

- Random access is extremely slow. To get to block n, the os has to start at the beginning and read the n - 1 blocks prior to it, one at a time.

- The amount of data source in a block is no longer a power of two because the pointer takes up a few bytes. Reads of the full block size require acquiring and concatenating information from two disk blocks, which generates extra overhead due to the copying.

Linked-list allocation using a table in memory

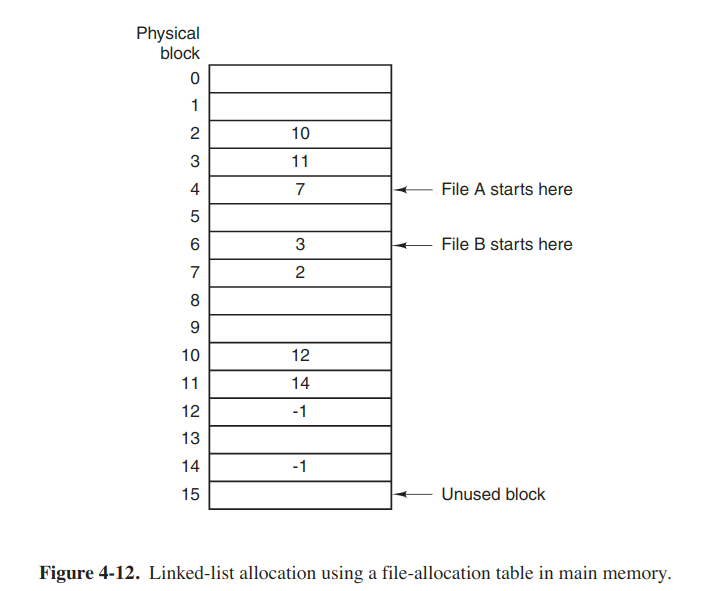

Both disadvantages of the linked-list allocation can be eliminated by taking the pointer word from each disk block and putting it in a table in memory. Following figure shows what the table looks like for the example of the above figure.

Such a table in main memory is called a FAT (File Allocation Table).

Random access is much easier. Although the chain must still be followed to find given offset within the file, the chain is entirely in memory, so it can be followed without making any disk references.

The primary disadvantage is that the entire table must be in memory all the time. With a 1-TB disk and a 1-KB block size, the table will take up 3 GB main memory all the time.

I-nodes

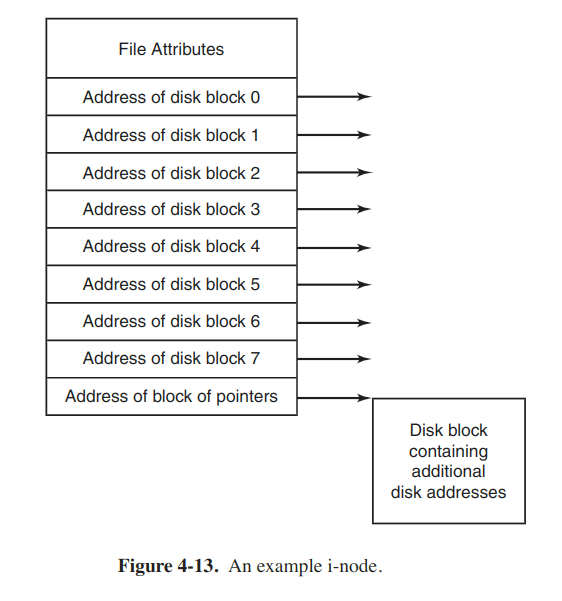

Every file is associated with a data structure called an i-node (index-node), which lists the attrs and disk addresses of the file's blocks. Given the i-node, it is possible to find all the blocks of the file.

The i-node need be in memory only when the corresponding file is open.

The problem with i-nodes is that if each one has room for a fixed number of disk addresses, it concerns when a file grows beyond the limit. One of the solutions is to replace the last disk address with the address of a block containing more disk-block addresses.

Implementing directories

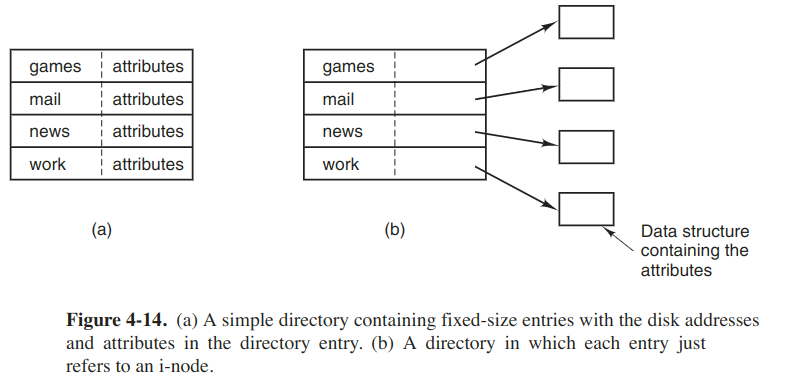

The main function of the directory system is to map the name of the file onto the info needed to locate the area. One obvious possibility is to store then directly in the directory entry, as shown in the following figure.

In this design, a directory consists of a list of fixed-size entries, one per file, containing a file name, a structure of the file attrs, and another disk addresses telling where the disk blocks are.

For the system using i-nodes, another possibility for storing the attrs is to store them in the inodes. Thus the directory entry can be shorter, only with a file name and an i-node number.

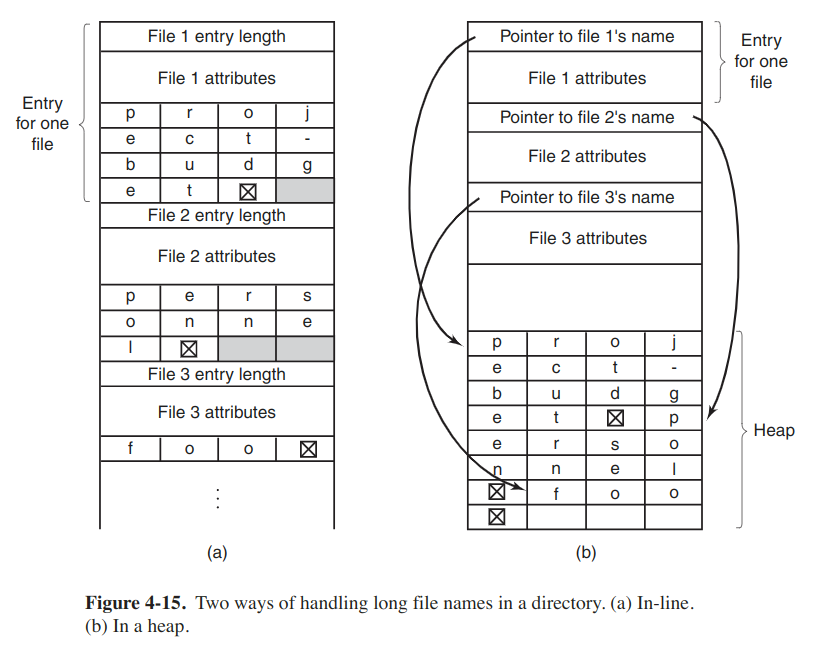

Then the problem comes to how to support longer, variable-length file names. Here are two approaches.

The disadvantange of the first method is that when a file is removed, a viriable-sized gap is introduced into the directory, which problem is essentially the same one we saw with contiguous disk files.

For extremely long directories, linear searching can be slow. One way to speed up is to use a hash table. In this way, lookup can be much faster, but administration will be more complex. A different way is to cache the results of searches.

Shared files

The basic method is to make a copy of the disk addresses of the original file when the file is linked. But changes made by someone will not be visible to the others, thus defeating the purpose of sharing. The problem can be solved in two ways.

In the first solution, disk blocks are in i-node (a little data structure) with the file itself. To make a link, the directory just point to the i-node. When deleting the original file, the only thing to do is remove directory entry, but leave the i-node intact.

The second solution is to create a new file of type LINK which contains just the path name of the file to which it is linked. This approach is called symbolic linking. When the owner removes the file, it is destroyed, and subsequent attempts to access the file via a sumbolic link will fail. However, symbolic links come with extra overhead. The file containing the path must be read, then the path must be parsed and followed, component by component, until the i-node is reached. All theses operations require a considerable number of disk accesses. Furthermore, an extra i-node is needed to for each symbolic link, as is an extra disk block to store the path. One of the advantages is that symbolic links can be used to link to files anywhere in the world, by simply providing the network address.

Log-structured file systems

The basic idea is to strcture the disk as a great big log. All writes are initially buffered in memory, and periodically all the buffered writes are written to the disk in a single segment, at the end of the log. Opening a file now consists of using the map, which is kept on disk and also cached, to locate the i-node. All of the blocks will be in segments, somewhere in the log.

However, real disks are finite, so eventually the log will occupy the entire disk. To deal with the problem, LFS hasa cleaner thread that scans the log circularly to compact it. It starts out by reading the summary of the first segment in the log to see which i-nodes and files are there. It then checks the i-node map to see if the i-nodes and file blocks are still in use. If not, that information is simply discarded. Else, these i-nodes and blocks go into memory to be written out in the next segment. Consequently, the disk is a big circular buffer.

Journaling file systems

The basic idea is to keep a log of what the file system is going to do before it does it, so that if the system crashes before it can do its planned work, upon rebooting the system can look in the log to see what was going on at the time of the crash and finish the job. NTFS, ext3 and ReFS all use jounaling.

What the system does is first write a log entry listing the actions to be completed. The log entry is then written to the disk (possibly read back from the disk to verify correctness). Only after the log entry has been written, do the various operations begin. After the operations complete successfully, the log entry is erased.

To make this work, the logged operations must be idempotent. And for added reliability, the system can introduce the database concept of an atomic transaction.

Virtual file systems

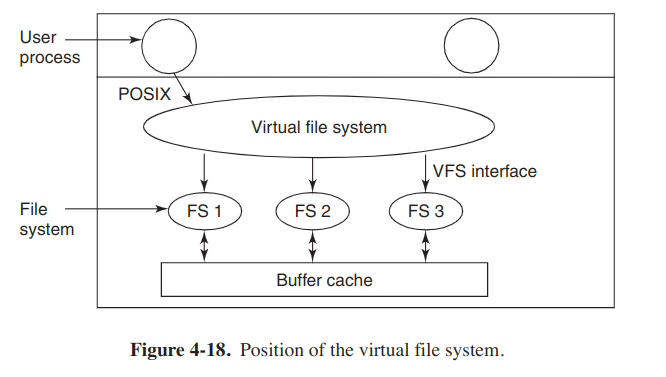

Most UNIX systems have used the concept of a VFS (virtual file system) to try to integrate multiple file systems into an orderly structure. The key idea is to abstract out that part of the file system that is common to all file systems and put that code in a separate layer that calls the underlying concrete file systems to actually manage the data.

The VFS has two distinct interfaces: the upper one to the user processes and the lower one to the concrete file systems. The original motivation to build the VFS was to support remote file systems using the NFS (Network FIle System) protocol.

Here is an example. When the system is booted, the root file system is registered with the VFS, and the other file systems are registered either at boot time or during operation. When a file system registers, it provides a list of the addresses of the functions that the VFS requires. The VFS then knows how to carry out every function the concrete file system must supply.

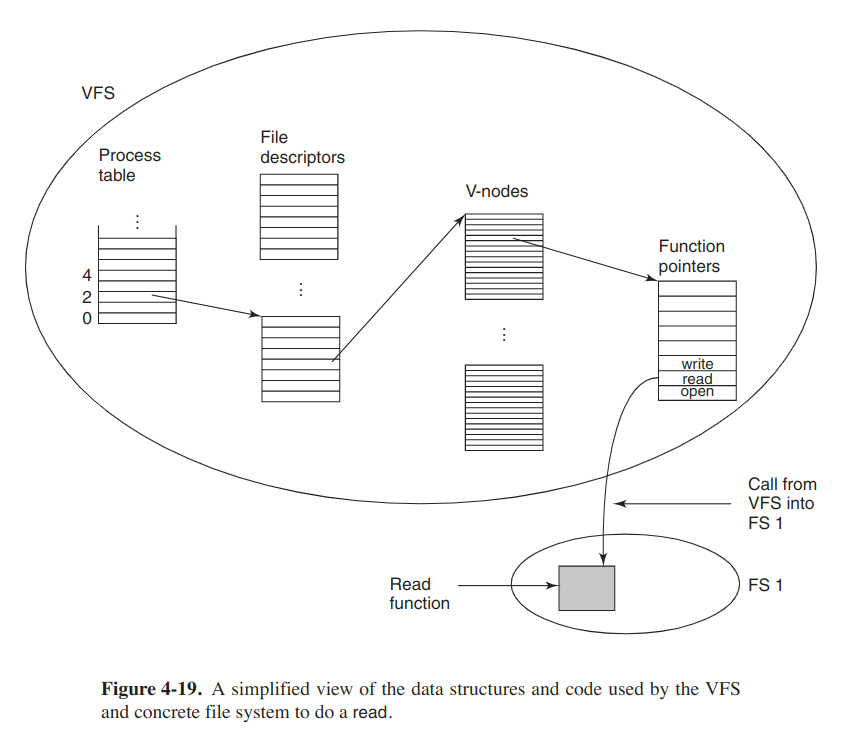

After a file system has been mounted, it can be used. When a process makes the call, open("/usr/include/unistd.h", O_RDONLY), the VFS sees that a file system has been mounted on /usr and locates its superblock by searching the list of the superblocks of mounted file systems. Having done this, it can find the root directory and look up the path include/unistd.h there. Then the VFS creates a v-node and makes a call to the mounted file system to return all the information in the i-node, and copy that into the v-node. After the v-node has been created, the VFS makes an entry in the file-descriptor table for the calling process and sets it to point to the v-node. Finally, the VFS returns the file descriptor to the caller so it can use it to read, write and do other operations.

Later when the process does a read using the fd, the VFS locates the v-node from the proccess and file descriptor tables and follows the pointer to the table of functions, all of which are addresses within the concrete file system. The function is now called and code within the concrete file system goes and gets the requested block.

Manangement and optimization

There are two general strategies for storing files: consecutive disk space being allocated, or the file is split up into several contiguous blocks. The same trade-off exists in memory-management between pure segmentation and paging. Nearly all file systems chop files up into fixed-size blocks that need not be adjacent for file growing.

Block size

The choice of block size is balance of performance and space utilization.

Keeping track of free blocks

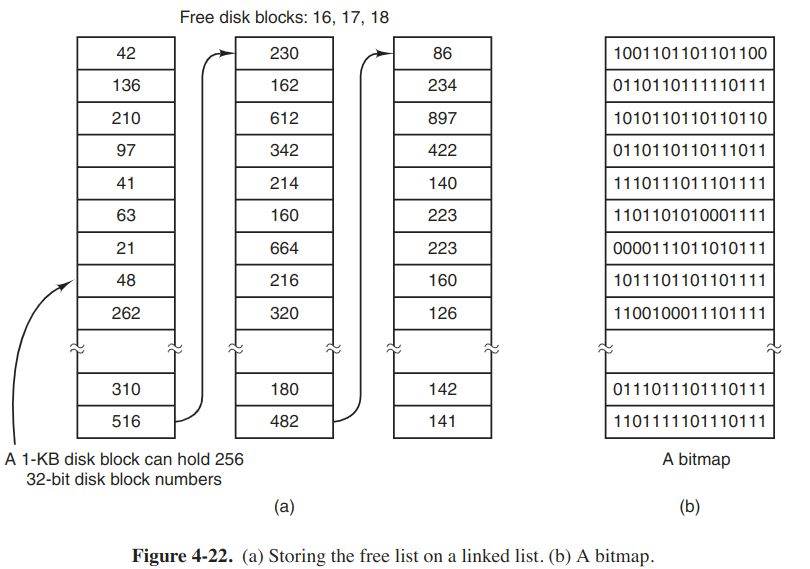

The first method consists of using a linked list of disk blocks, with each block holding as many free disk block numbers as will fit. With a 1-KB block and a 32-bit disk block number, each block on the free list holds the number of 255 free blocks. The other technique is the bitmap. For 1-TB disk, we need around 130,000 1-KB blocks to store.

If free blocks tend to come in long runs of consecutive blocks, the free-list system can be modified to keep track of runs of blocks rather than single blocks. But if the disk becomes severely fragmented, keeping track of runs is less efficient than keeping track of individual blocks.

File-system performance

Caching

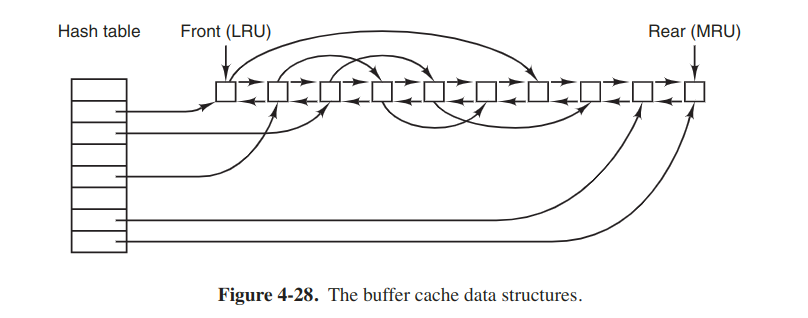

The most common technique used to reduce disk accesses is the block cache or buffer cache.

When a block has to be loaded into a full cache, some block has to be removed. The situation is like paging, and all the usual page-replacement algorithms described there are applicable. There is also a bidirectional list running through all the blocks in the order of usage. The implementation is the same like exact LRU.

However, the problem has to do with the crashes and file-system consistency. When a block is read and modified, it may be quite a while before it reaches the front (as the least recently used block) and is written to the disk. Besides, some blocks, such as i-node blocks, are rarely referenced within a short interval. These two situations should be considered.

For both questions, blocks can be divided into categories. Blocks that will probably not be needed again soon go on the front, rather than the rear of the LRU list.

If the block is essential to the file-system consistency and has been modified, it should be written to disk immediately. And systems take two approaches to dealing with data blocks. The UNIX way is to have a system call, sync, which forces all the modified blocks out onto disk immediately. When the system is started up, a program, usually called update, is started up in the background to sit in an endless loop issuing sync calls. What Windows did was to write every modified block to disk as soon as it was written to the cache. Caches in which all modified blocks are written back to disk immediately are called write-through caches.

Block read ahead

The technique is to try to get blocks into the cache before they are needed to increase the hit rate. The read-ahead strategy works only for files that are actually being read sequentially.

Reducing disk-arm motion

The technique is to reduce the amount of disk-arm motion by putting blocks that are likely to be accessed in sequence close to each other, preferably in the same cylinder.

If the free blocks are recorded in a bitmap, and the whole bitmap is in memory, it is easy to choose a free block as close as possible to the previous block. With a free-list, some block clustering can be done. The trick is to keep track of disk storage in groups of consecutive blocks: allocate disk storage in units of multi blocks.

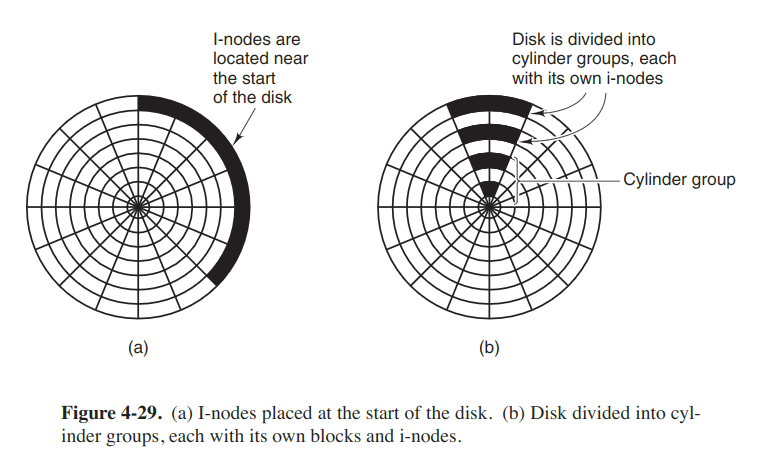

Another performance bottleneck in systems that use i-nodes is that reading even a short file requires two disk accesses: one for the i-node and one for the block. One easy performance improvement is to put the i-nodes in the middle of the disk rather than at the start.