OS Notes: Linux

Table of Contents

Processes

Impl of processes and threads

Processes

The Linux kernel internally represents processes as tasks, via the structure task_struct. Linux uses the task structure to represent any execution context.

For each process, a process descriptor of type task_struct is resident in memory at all times. It contains vital information needed for the kernel's management of all processes. The process descriptor along with memory for the kernel-mode stack for the process are created upon process creation.

For compatibility with other UNIX systems, Linux identifies processes via the PID. The kernel organizes all processes in a bidirectional linked-list of task structures. The PID can be mapped to the address of the task structure in order to access the info directly.

The task structure contains a variety of fields. Some of these fields contain pointers to other data structures or segments, which may be related to the user-level structure of the process, which is not interest when the user process is not runnable. Thereforce, these may be swapped or paged in order not to waste memory. However, info about signals must be in memory all the time, even when the process is not present in memory, while file descriptors can be kept in the user structure and brought in only when the process is in memory and runnable.

The info in the process descriptor falls into a number of broad categories that can be roughly described as follows:

- Scheduling parameters which are used to determine which process to run next.

- Memory image with pointers to the text, data, and stack segments, or page tables.

- Signals.

- Machine registers are used to save registers when a trap to the kernel occurs.

- System call state.

- File descriptor table.

- Accounting as a pointer to a table that keeps track of the user and system CPU time used by the process and other info.

- Kernel stack is a fixed stack for use by the kernel part of the process.

- Miscellaneous. Current process state, PID, parent process PID, user and group identification and so on.

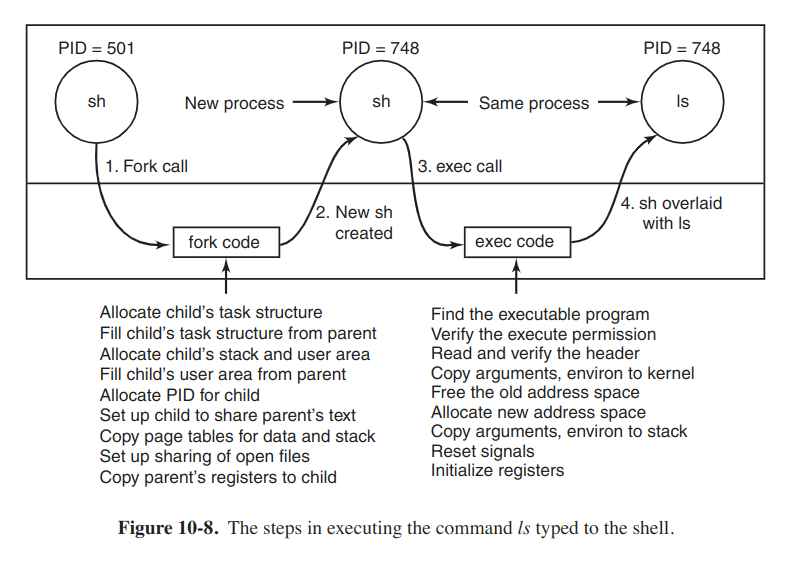

When a fork system call is executed, the calling process traps to the kernel and creates a task structure and few other accompanying data structures, such as kernel-mode stack and a thread_info structure. This structure is allocated at a fixed offset from the process' end-of-stack, and contains few process parameters, along with the address of the process descriptor.

The majority of the process descriptor contents are filled out based on the parent's descriptor values. The system then looks for an available PID and updated the PID hash-table entry to point to the new task structure. It also sets the fileds in the task_struct to point to the previous/next process on the task array.

Here with the mechanism called copy on write, the child process is given its own page tables, but have them point to the parent's pages, only marked read only. Whenever either parent/child process tries to write on a page, it gets a protection fault. The kernel then allocates a new copy of the page to the faulting process and marks it read/write.

When a exec system call is executed then, the kernel finds and verifies the executable file, copies the arguments and enviroment strings to the kernel, and releases the old address space and its page table. Now the new address space must be created and filled in. If the system supports mapped files, the new page tables are set up to indicate that no pages are in memory, except perhaps one stack page, but that the address space is backed by executable file on disk. When the new process starts running, it will get a page fault, which will cause the first page of code to be paged in from the executable file. In this way, nothing has to be loaded in advance, so programs can start quickly and fault in just those pages they need and no more. Finally, the arguments and environment strings are copied to the new stack, the signals are reset, and the registers are initialized to all zeros.

Threads

Here just focus on kernel threds in Linux, particalarly on the differences among the Linux thread model and other Unix systems. There are several challenging decisions present.

Linux introduced a powerful new system call, clone, that blurred the distinction between processes and threads. The signature is as follws:

int clone(int (*fn)(void *), void *stack, int flags, void *arg);

// return pid

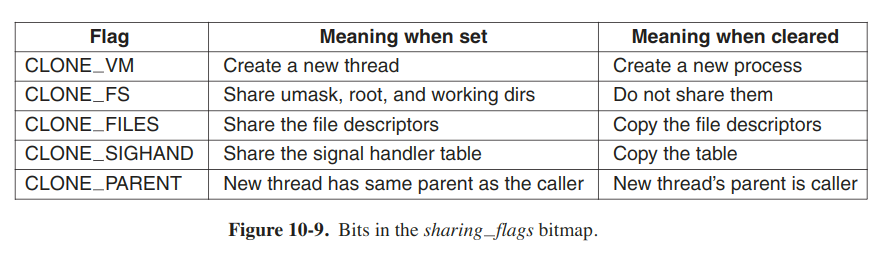

The flags parameter is a bitmap that allows a finer grain of sharing than UNIX systems. Each of the bits can be set indelendently of the other ones.

The fine-grained sharing is possible because Linux maintains separate structures for the various items. The task structure just points to these data structures, so it is easy to make a new task structure for each cloned thread and have it point either to the old thread's scheduling, memory, and other data structures or to copies of them.

To be compatible with othe UNIX systems, Linux distinguishes between PID and a task identifier (TID). Both fields are stored in the task structure. When clone is used to create a new process that shares nothing with its creator, PID is set to a new value; otherwise the task receives a new TID, but inherits the PID.

Scheduling

To start with, Linux threads are kernel threads, so scheduling is based on threads but not processes. Linux distinguishes three classes of threads for scheduling purposes:

- Real-time FIFO.

- Real-time round robin.

- Timesharing.

Real-time FIFO threads are the highest prioroty and are not preemptable except by a newly ready real-time FIFO thread with higher priority. Real-time round robin threads are the same as real-time FIFO threads except that they have time quanta associated with them, and are preemptable by the clock. If multiple real-time round-robin threads are ready, each one is run for its quantum, after which it goes to the end of the list of real-time round-robin threads. Neither of these classes is actually real time in any sense. The reason they are called real time is that Linux is conformant to the P1003.4 standard which uses those names. These threads are internally represented with priority levels from 0, which is the highest, to 99.

Non-real-time threads from a separate class and are scheduled by a separate algorithm. Internally, these threads are associated with priority levels from 100 to 139.

Like most UNIX systems, Linux associates a nice value with each thread, which ranges from -20 to +19.

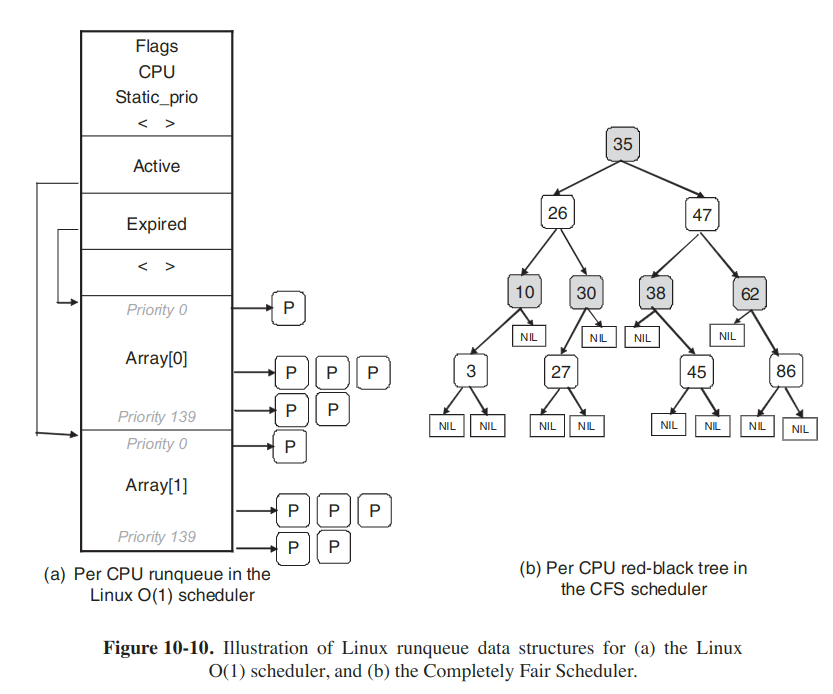

Linux scheduling algorithms are closely related to the design of the runqueue, a key data structure used by the scheduler to track all runnable tasks in the system and select the next one to run. A runqueue is associated with each CPU in the system.

A popular Linux scheduler was the Linux O(1) scheduler. The runqueue is organized in two arrays, active and expired. Each of these is an array of 140 list heads, each correpsonding to a different priority. Each list head points a doubly linked-list of processes at a given priority. The basic operation can be described as follows.

The scheduler selects a task from the highest-priority list in the active array. If that task's quantum (timeslice) expires, it is moved to the expired list (potentially at a different priority level). If the task blocks, for instance to wait on an I/O event, before its timeslice expires, once the event occurs and its excution can resume, it is placed back on the original active array, and its timeslice is decremented to reflect the CPU time it already used. Once its timesplice is fully exhausted, it, too, will be placed on the expire array. When there are no more tasks in the active array, the scheduler simply sways the pointers, so the expired arrays now become active, and vice versa.

Here different priority levels are assigned different timeslice values, with higher quanta assigned to higher-priority processes.

Since Linux does not know a priori whether a task is I/O- or CPU-bound, it relies on continuously maintaing interactivity heuristics. In this manner, Linux distinguishes between static and dynamic priority. The threads' dynamic priority is continuously recalculated, so as to (1) reward interactive threads, and (2) punish CPU-hogging threads. The scheduler maintains a sleep_avg variable associated with each task. Whenever a task is awakened, this variable is incremented. Whenever a task is preempted or when its quantum expires, this variable is decremented by the corresponding value. This value is used to dynamically map the task's bonus to values from -5 to +5. The scheduler recalculates the new priority level when a thread is moved from the active to the expired list.

Most notably, the heuristics used to determine the interactivity of a task, and therefore its priority level, were complex and imperfect, and resulted in poor performance for interactive tasks. To address the issue, a new scheduler called Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS) is proposed.

The main idea is to use a red-black tree as the runqueue data structure. Tasks are ordered in the tree based on the amount of time they spend running on the CPU, called vruntime. CFS accounts for the tasks' running time with nanosecond granularity. Each internal node in the tree corresponds to a task. The children to the left correspond to tasks which had less time on the CPU, and therefore will be scheduled sooner, and the children to the right on the node are those that have consumed more CPU time thus far.

The scheduling algorithm can be summarized as follows. CFS allows schedules the task which has had least amount of time on the CPU, typically the leftmost node in the tree. Periodically, CFS increments the task's vruntime value base on the time it has already run, and compares this to the current leftmost node in the tree. If the running task still has the smaller vruntime, it will continue to run. Otherwise, it will be inserted at the appropriate place in the red-black tree, and the CPU will given to task corresponding to the new leftmost node.

To account for differences in task priorities and niceness, CFS changes the effictive rate at which a task's virtual time passes when it is running on the CPU. For lower-priority tasks, time passes more quickly, and they will lose the CPU and be reinserted in the stree sooner. In this manner, CFS avoids using separate runqueue structures for different priority levels.

The Linux scheduler includes special features particularly useful for multiprocessor or multicore platforms.

- The runqueue structure is associated with each CPU. The scheduler tries to maintain benefits from affinity scheduling, and to schedule tasks on the CPU on which they were previously executing.

- A set of system calls is available to further specify or modify the affinity requirements of a select thread.

- The scheduler performs periodic load balancing across runqueues of different CPUs to ensure that the system load is well balanced, while still meeting certain performance or affinity requirements.

Tasks which are not runnable and are waiting on various I/O operations or other kernel events are placed on another data structure, waitqueue. A waitqueue is associated with each event that tasks may wait on. The head of the quue includes a pointer to a linked list of tasks and a spinlock. The spinlock is necessary so as to ensure that the waitqueue can be concurrently manipulated through both the main kernel code and interrupt handlers or other async invocations.

Booting

When the computer starts, the BIOS performs Power-On-Self-Test (POST) and initial device discovery and initialization, since the OS' boot process may rely on access to disks, screens, keyboards, and so on. Next, the first sector of the boot disk, the MBR (Master Boot Record), is read into a fixed memory location and executed. This sector contains a small program that loads a standalone program called boot from the boot device. The boot program first copies itself to a fixed high-memory address to free up low memory for the os. Once moved, boot reads the root directory of the boot device. To do this, it must understand the file system and directory format, which is the case with some bootloaders such as GRUB (GRand Unified Bootloader). They need a block map and low-level addresses, which describe physical sectors, heads, and cylinders, to find the relevant sectors to be loaded. Then boot reads in the os kernel and jumps to it. At this point, it has finished its job and the kernel is running.

The kernel start-up code is written in assembly language and is highly machine dependent. Typical work includes setting up the kernel stack, identifying the CPU type, calculating the amount of RAM present, disable interrupts, enabling the MMU, and finally calling the C-language main procedure to start the main part of the os.

The C code also has considerable initialization to do, but this is more logical than physical. It starts out by alocating a message buffer to help debug boot problems. Next the kernel data structures are allocated. A few of them, such as the page cache and certain page table structures, depend on the amount of RAM avialable. At the point the system begins autoconfiguration. Using configuration files teling what kinds of I/O devices might be present, it begins probing the devices to see which ones actually are present. If a probed device responds to the probe, it is added to a table of attached devices. Unlike traditional UNIX versions, Linux device drivers do not need to be statically linked and may be loaded dynamically.

Once all the hardware has been configured, the next thing to do is to carefully handcraft process 0, set up its stack, and run it. Process 0 continues initialization, doing things like programming the real-time clock, mounting the root file system, and creating init (process 1) and the page daemon (process 2).

Init checks its flags to see if it is supposed to come up single user or multiuser. In the former case, it forks off a process that executes the shell and waits for this process to exit. In the latter case, it forks off a process that executes the system initialization shell script which can do file system consistency checks, mount additional file systems, start daemon processes, and so on.

Memory management

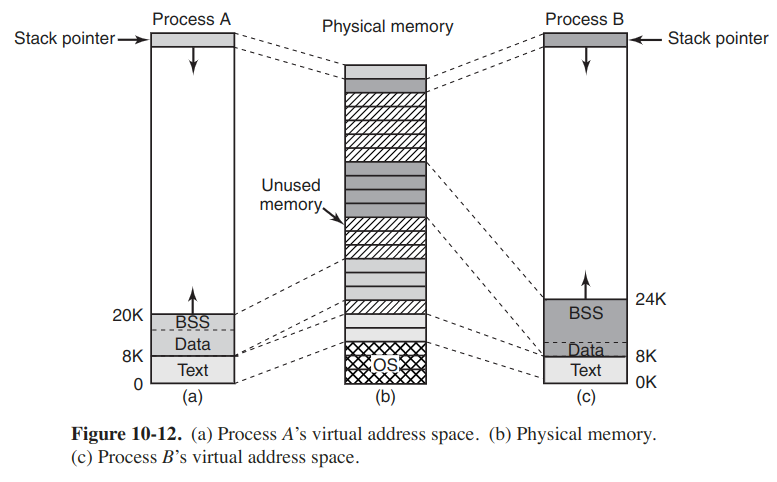

Every Linux process has an address space that logically consists of three segments: text, data, and stack. The text segment contains the machine instructions that form the program's executable code. The data segment contains storage for all the program's variables, strings, arrays and other data. It has two parts, the initialized data and the uninitialized data, which is known as the BSS (historically called Block Started by Symbol). All the variables in the BSS part are initialized to zero after loading.

In order to avoid allocating a physical page frame full of zeros, during initialization Linux alocates a static zero page, a write-protected page full of zeros. When a process is loaded, its unitialized data region is set to point to the zero page. Whenever a process actually attempts to write in this area, the copy-on-write mechanism kicks in, and an actual page frame is allocated to the process.

Unlike the text segment, the data segment can change. Many programs need to allocate space dynamically, during execution. Linux handles this by permitting the data segment to grow and shrink as memory is allocated and deallocated. A system call, brk, is available to allow a program to set the size of its data segment, The process address-space descriptor contains information on the range of dynamically allocated memory areas in the process, typically called the heap.

On most machines, the stack segment starts at or near the top of the virtual address space and grows down toward 0. If the stack grows the bottom of the stack segment, a hardware fault occurs and the os lowers the bottom of the stack segment by one page.

When a program starts up, its stack is not empty. Instead it contains all the environment (shell) variables as well as the command line typed to the shell to invoke it.

When two users are running the same program, Linux systems support shared text segments.

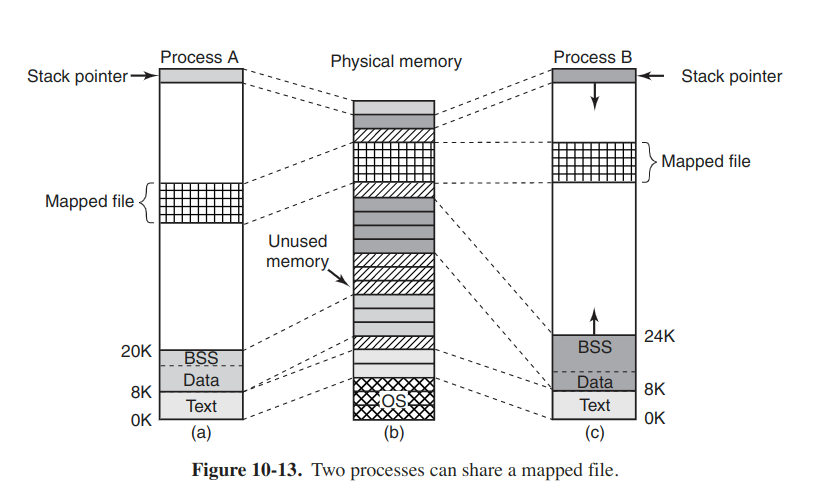

In additionally dynamically allocating more memory, processes in Linux can access file data through memory-mapped files. This feature makes it possible to map a file onto a portion of a process' address space so that the file can be read and written as if it were a byte array in memory. Mapping a file in makes random access to it much easier than using I/O system calls such as read and write. Another advantage is that two or more processes can map in the same file at the same time. Writes to the file by any one of them are then instantly visible to the others. In fact, the mechanism provides a high-brand-width way for multiple processes to share memory.

System calls

In practice, most Linux systems have system calls for managing memory.

| System call | Description |

|---|---|

| s = brk(addr) | Change data segment size |

| a = mmap(addr, len, prot, flags, fd, offset) | Map a file in |

| s = unmap(addr, len) | Unmap a file |

Implementation

Physical memory management

Due to idiosyncratic hardware limitations on many systems, not all physical memory can be treated identically, especially with respect to I/O and virtual memory. Linux distinguishes between the following memory zones:

- ZONE_DMA and ZONE_DMA32: pages that can be used for DMA.

- ZONE_NORMAL: normal, regularly mapped pages.

- ZONE_HIGHMEM: pages with high-memory addresses, which are not permanently mapped.

Main memory in Linux consits of three parts. The first parts, the kernel and memory map, are pinned in memory (never paged out). The rest of memory is divided into page frames, each of which can contain a text, data, or stack page, a page-table page, or be on the free list.

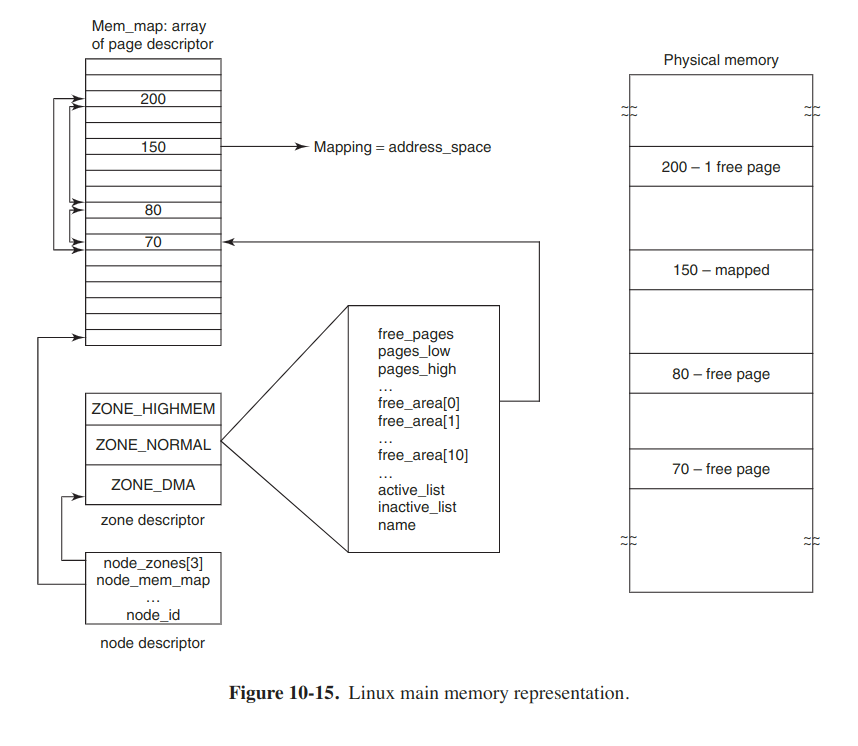

The kernel maintains a map of the main memory which contains all information about the use of the physical memory in the system, such as its zones, free frames and so forth.

Linux maintains an array of page descriptors, of type page one for each physical page frame in the system, called mem_map. Each page descriptor contains a pointer to the address space that it belongs to, in case the page is not free, a pair of pointers which allow it to form doubly linked lists with other descriptors, for instance to keep together all free page frames, and a few other fields.

Since the physical memory is divided into zones, for each zone Linux maintains a zone descriptor, which contains information about the memory utilization within each zone, such as number of active or inactive pages.

Finally, since Linux is portable to NUMA architectures, in order to differentiate between physical memory on different nodes, a node descriptor is used. Each descriptor contains info about memory usage and zones on the particular node. On UMA platforms, Linux describes all memory via one node descriptor.

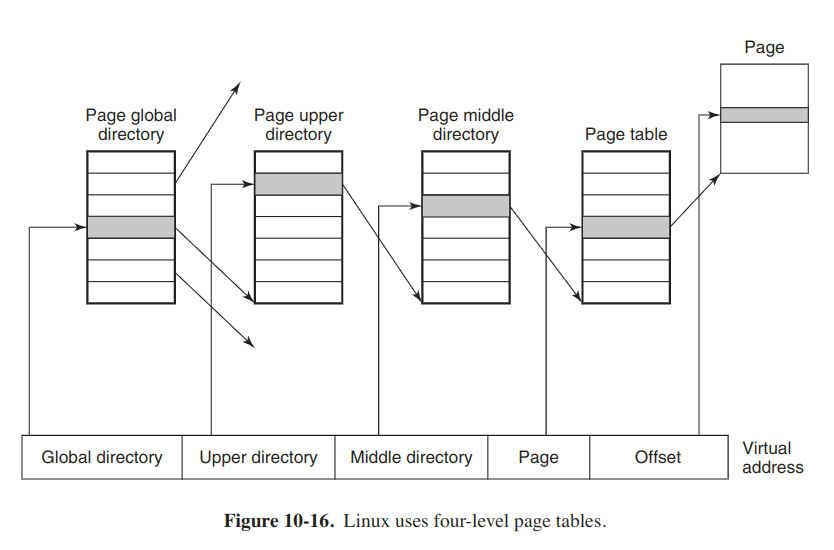

In order for the paging mechanism to efficient on both 32- and 64-bit architectures, Linux make use of a four-level paging scheme. Each virtual address is broken up into five fields.

Physical memory is used for various purposes. The kernel itself is fully hard-wired; no part of it is ever paged out. The rest of memory is available for user pages, the paging cache, and other purposes. The page cache holds pages containing file blocks that have recently been read or have been read in advance in expectation of being used in the near future, or pages of file blocks which need to be written to disk. It is dynamic in size and competes for the same pool of pages as the user processes. The paging cache is not really a separate cache, but simply the set of user pages that are no longer needed and are waiting around to be paged out.

Memory-allocation mechanisms

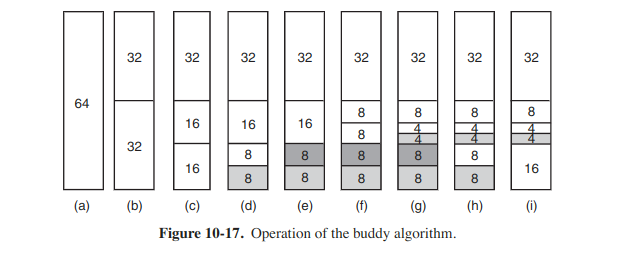

The main mechanism for allocating new page frames of physical memory is the page allocator, which operates using the well-known buddy algorithm.

The memory that consists of 64 pages operates as follows:

The algorithm leads to considerable internal fragmentation because if you want a 65-page chunk, you have to ask for and get a 128-page chunk. So the slab allocator comes. The allocator takes chunks using the buddy algorithm but then carves slabs from them and manages the smaller units separately.

Since the kernel frequently creates and destroys objects of certain type, it relies on so-called object caches. These caches consist of pointers to one or more slab which can store a number of objects of the same type. Each the slabs may be full, partiall full, or empty. The kmalloc kernel service is built on top of the slab and object cache interface.

Vmalloc is used when the requested memory need be contiguous only in virtual space. It is used primarily for allocating large amounts of contiguous virtual address space, such as for dynamically inserting kernel modules.

Virtual address-space representation

The virtual address space is divided into homogeneous, contiguous, page-aligned areas or regions. Each area consists of a run of consecutive pages with the same protection and paging properties. Each area is described in the kernel by a vm_area_struct entry. All structs for a process are linked together in a list sorted on virtual address. When the list gets too long, a tree is created to speed up searching it.The vm_area_struct entry lists the area's properties. These properties include the protection mode, whether pinned in memory, and which direction it grows in, and so on.

A top-level memory descriptor, mm_struct, gathers info about all virtual-memory areas belonging to an address space, info about the different segments, about users sharing this address space, and so on. All vm_area_struct elements of an address space can be accessed through their memory descriptor in two ways. One of the methods is oroganizing them in linked lists, and the other is in a binary red-black tree.

Paging

The main memory management unit is a page for Linux, and almost all memory-management components operate on a page granularity. The swapping subsystem also operates on page granularity and is tightly coupled with the page reclaiming algorithm.

The basic idea behind paging is simple: a process need not be entirely in memory in order to run. If the user structure and the page tables are swapped in, the process is deemed "in memory" and can be scheduled to run. The pages of the text, data, and stack segments are brought in dynamically, one at a time, as they are referenced.

Paging is implemented partly by the kernel and partly by a new process called the page daemon.

Linux is a fully demand-paged system with no prepaging and no working-set concept (although there is a call in which a user can give a hint that a certain page may be needed soon). Text segments and mapped files are paged to their respective files on disk. Everything else is paged to either the paging partition or one of the fixed-length paging files, called the swap area.

Paging to a separate partition, accessed as a raw device, is more effecient than paging to a file for several reasons.

- The mapping between file blocks and disk blocks is not needed.

- the physical writes can be of any size, not just the file block size.

- A page is always written contiguous to disk; with a paging file, it may or may not be.

The page replacement algorithm

The PFRA (Page Frame Reclaiming Algorithm) algorithm tries to keep some pages free so that they can be claimed as needed.

Linux distinguishes between four different types of pages: unreclaimable, swappable, syncable, and discardable. Unreclaimable pages may not be paged out. Swappable pages must be written back to the swap area or the paging disk partition before the page can be reclaimed. Syncable pages must be written back to disk if they have been marked as dirty. Discardable pages can be reclaimed immediately.

At boot time, init starts up a page daemon, kswapd, for each memory node, and configures them to run periodically. It can be awakened early if more pages are suddenly needed also. Each time awakened, it checks to see if there are enough free pages available, by comparing the low and high watermarks with the current memory usage for each memory zone. If the available memory for any of the zones ever falls below a threshold, kswapd initiates the page frame reclaiming algorithm. There are typically max to 32 pages being reclaimed during each run, which control the I/O pressure.